The first thing I did when looking at this page was do a quick google search of William W. Harding. I found that he was the publisher of the Philadelphia Inquirer newspaper from 1859 to 1889. The paper was founded in 1829 and purchased soon after by Harding’s father Jasper. It was then called the Pennsylvania Inquirer. Like a good capitalist, Jasper expanded the business by purchasing newspapers in the region – all printed on flat-bed presses, the direct descendant of Gutenberg’s press. His son William White Harding took over in 1859 and changed the name to the Philadelphia Inquirer and upgraded the press to a Bullock steam press. This was a rotating press developed by William Bullock, also of Philadelphia. The rotating press allowed continuous printing onto rolls of paper. This type of printing press was invented in 1814 by a German living in England and was taken up by the Times of London which ensured its adoption widely. The steam driven rotating press was developed in the U.S. in 1843. Bullock further improved the technology in such a way that allowed printing on both sides of the paper at the same time and also automatically folded and cut it into sheets. Thus the wonder of capitalism and technology so opposed by the Left today. When the Times changed over, their printers threatened violence, but the company promised them other jobs, ending the threat. Thus the wonder of organized Labour softening capitalism and technology. The Bullock press could print 12,000 sheets an hour and with later improvements that increased to 30,000 sheets. Today newspapers are shedding their printing operations to go online, or consolidating them into central locations for a number of publications owned by large corporations. Of course, this is what the Hardings did in the 19th century too. The difference is that the employees losing their jobs are not being moved elsewhere in their respective companies. A change in how information is disseminated is underway and has been underway for a number of years now. But, in the 19th century, printing presses were the technology of the day and still had a century and more to dominate how information was spread.

The first thing I did when looking at this page was do a quick google search of William W. Harding. I found that he was the publisher of the Philadelphia Inquirer newspaper from 1859 to 1889. The paper was founded in 1829 and purchased soon after by Harding’s father Jasper. It was then called the Pennsylvania Inquirer. Like a good capitalist, Jasper expanded the business by purchasing newspapers in the region – all printed on flat-bed presses, the direct descendant of Gutenberg’s press. His son William White Harding took over in 1859 and changed the name to the Philadelphia Inquirer and upgraded the press to a Bullock steam press. This was a rotating press developed by William Bullock, also of Philadelphia. The rotating press allowed continuous printing onto rolls of paper. This type of printing press was invented in 1814 by a German living in England and was taken up by the Times of London which ensured its adoption widely. The steam driven rotating press was developed in the U.S. in 1843. Bullock further improved the technology in such a way that allowed printing on both sides of the paper at the same time and also automatically folded and cut it into sheets. Thus the wonder of capitalism and technology so opposed by the Left today. When the Times changed over, their printers threatened violence, but the company promised them other jobs, ending the threat. Thus the wonder of organized Labour softening capitalism and technology. The Bullock press could print 12,000 sheets an hour and with later improvements that increased to 30,000 sheets. Today newspapers are shedding their printing operations to go online, or consolidating them into central locations for a number of publications owned by large corporations. Of course, this is what the Hardings did in the 19th century too. The difference is that the employees losing their jobs are not being moved elsewhere in their respective companies. A change in how information is disseminated is underway and has been underway for a number of years now. But, in the 19th century, printing presses were the technology of the day and still had a century and more to dominate how information was spread.

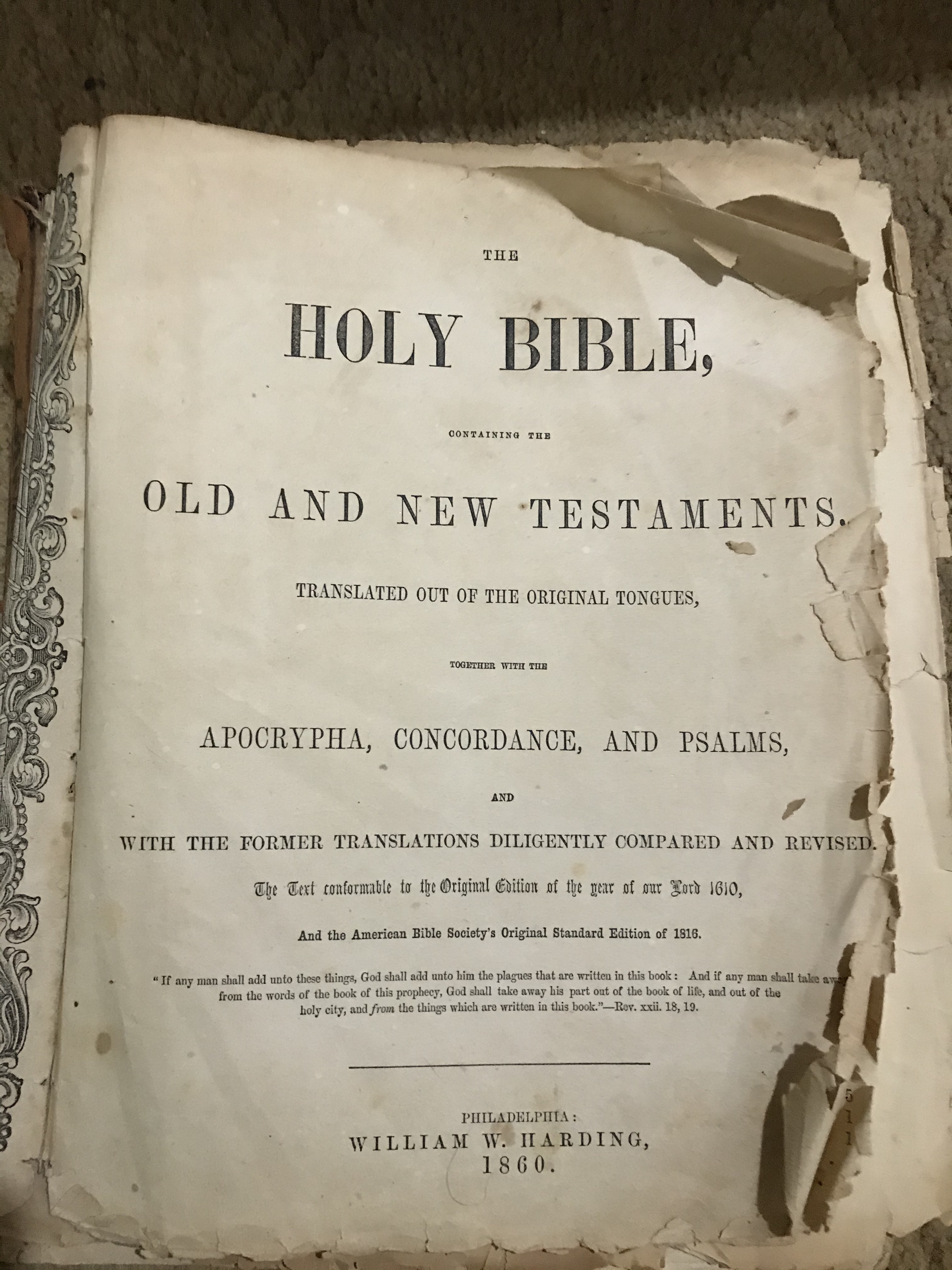

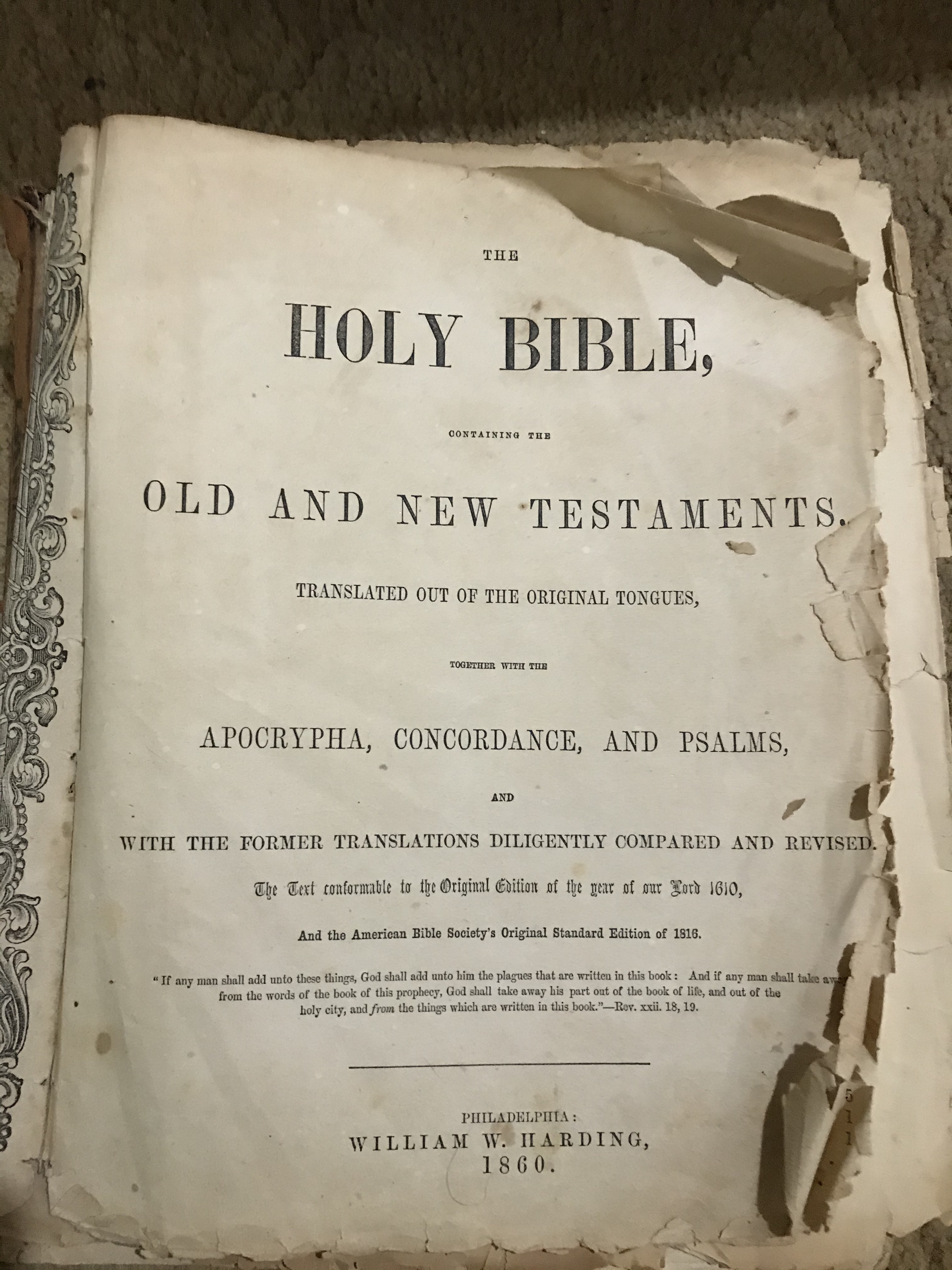

The Bible above is dated to 1860, the second year that William W. Harding ran the company. I wonder were Bibles a money maker? Business men were Christians then and combined their Christianity with their business world. I saw this while working on my PhD dissertation and while writing entries for a local historical project, The Dictionary of Hamilton Biography. Business men (and they were all men) belonged to several clubs, including their church. Working class men might or might not belong to one of the early union organizations such as the Knights of Labour, but did have their own churches as well. English-speaking Canada and most of the Anglosphere was dominated by Protestant Christianity, for which the Bible was central. Political speeches, newspaper articles and reports, novels, poetry, were all peppered with Biblical references that were commonly understood. All of this, of course, began to fall apart in the 1960s, but that is a subject for the last two entries of this series of blog posts. In 1860, the Bible was the book both in terms of religion and in terms of cultural norms. If a person had read no other book, that person had read at least parts of the Bible and understood Biblical references.

This volume lacks a cover or back, but still has the spine holding it all together, which brings to mind the old metaphor about needing a backbone to withstand the vicissitudes of life. Harding was a good example of what used to be called ‘Yankee ingenuity’, combined with family inheritance. He changed the name of his inherited newspaper to the Philadelphia Inquirer, perhaps a reflection of the growth of urbanism and its concomitant pride in one’s city. He updated the technology at the same time and began to print Bibles in 1860. He sold the business in 1889 just prior to his death, but the new owners continued in the same vein.

This particular copy belonged to my maternal grandmother’s mother. My maternal grandmother had the maiden name Bates and her mother’s maiden name was Wright. Thus, this is the Wright family Bible. In the section dividing the Old and New Testaments of these very large, family Bibles, there are pages for writing in marriages, births and deaths. Family and Christianity were in the same fashion as business and Christianity, an integral whole. These Bibles usually included plates of images of Biblical scenes – I wonder if research has been done on the artists who drew the pictures? I would guess a book could be written about these large Bibles. These books must have had pride of place in a house as they are large – the three copies I have are roughly 11 x 9 inches and about 3 – 4 inches thick – let me translate that to metric: 28 cm x 23 cm and 10 cm thick. They have heavy bound covers and spines and often a metal clasp to hold the book shut. This 1860 copy is missing both the front and back covers, but still has the heavy back attached. They are sewn, not glued as well. They scream permanence and solidity.

Our civilization’s artifacts say much in a language that few speak today in a conscious fashion, saying different things at different points in history. 1860 was a time where solidity, permanence, and confidence nestled within technological change, or rather technological change did not challenge faith. Technological change served the Biblical foundation. Bibles were designed to last and to represent the foundation of social relations – reminding all of the teachings about building on a rock, not shifting sand. If you click on this link, you will see I used the King James translation as would be proper for 1860.

This was a society linked corporately by an inchoate and at the same time, learned knowledge of the Bible in its King James version in the English-speaking world. This Bible represents a world now lost where faith was integrated into all aspects of life, whether you actually believed the doctrines or not. There were Catholics who shared in this but who were on the outside to a degree, though the translation used in 1860, the Douay/Rheims had much the same form of English. This was a Protestant world where Catholics were on the outside, and non-Christians barely acknowledged, though in the 19th century the only non-Christians the majority had any awareness of were Jews.

Bibles as artifacts represented a world where language, architecture, education, science, technology, social relations, entertainment aspired to a formality (not always achieved – there is a good literature on drinking culture in this period) as an ideal. A sense of permanence permeated life, which I suppose made the frantic and seemingly sudden changes of the second haf of the 20th century all the more startling when they came.

For this year, Anno Domini 2020 I chose a screenshot of the way the Bible appears in this cyber era. This is an evangelical Protestant site where one can find many Bible translations and also a search box. I noticed that the default translation is the King James version. In the post on the 60s I noted that this translation was the translation for the English-speaking world, even to influencing Catholic Bibles from the 18th century into the present day.

For this year, Anno Domini 2020 I chose a screenshot of the way the Bible appears in this cyber era. This is an evangelical Protestant site where one can find many Bible translations and also a search box. I noticed that the default translation is the King James version. In the post on the 60s I noted that this translation was the translation for the English-speaking world, even to influencing Catholic Bibles from the 18th century into the present day.

The first thing I did when looking at this page was do a quick google search of William W. Harding. I found that he was the publisher of the Philadelphia Inquirer newspaper from 1859 to 1889. The paper was founded in 1829 and purchased soon after by Harding’s father Jasper. It was then called the Pennsylvania Inquirer. Like a good capitalist, Jasper expanded the business by purchasing newspapers in the region – all printed on flat-bed presses, the direct descendant of Gutenberg’s press. His son William White Harding took over in 1859 and changed the name to the Philadelphia Inquirer and upgraded the press to a Bullock steam press. This was a rotating press developed by William Bullock, also of Philadelphia.

The first thing I did when looking at this page was do a quick google search of William W. Harding. I found that he was the publisher of the Philadelphia Inquirer newspaper from 1859 to 1889. The paper was founded in 1829 and purchased soon after by Harding’s father Jasper. It was then called the Pennsylvania Inquirer. Like a good capitalist, Jasper expanded the business by purchasing newspapers in the region – all printed on flat-bed presses, the direct descendant of Gutenberg’s press. His son William White Harding took over in 1859 and changed the name to the Philadelphia Inquirer and upgraded the press to a Bullock steam press. This was a rotating press developed by William Bullock, also of Philadelphia.  I was intrigued by the complexity, but not seduced. I think, perhaps, the complexity hid a hollow centre.

I was intrigued by the complexity, but not seduced. I think, perhaps, the complexity hid a hollow centre. I was searching through this biography of J.R.R. Tolkien today, looking for a particular reference. I didn’t find the reference, but perhaps it was not in the biography but somewhere else. The picture of Prof. Tolkien puffing thoughtfully on his pipe is a good depiction of why I wanted to find this reference, which is an anecdote about an academic battle fought by Tolkien and his friend C.S. Lewis. They did not want Oxford to introduce what they called ‘the research degree’ (the doctorate) into the faculty of English. They felt it had no place in the study of English, whether language or literature. Research, they thought, was not what scholars in the Humanities, or at least in the English faculty, did. Scholars had mastered their discipline, that is, they had read and meditated on, discussed with others, all that had been written in their field and this was evidenced by the M.A. degree. They then wrote the results of their meditations and discussions.

I was searching through this biography of J.R.R. Tolkien today, looking for a particular reference. I didn’t find the reference, but perhaps it was not in the biography but somewhere else. The picture of Prof. Tolkien puffing thoughtfully on his pipe is a good depiction of why I wanted to find this reference, which is an anecdote about an academic battle fought by Tolkien and his friend C.S. Lewis. They did not want Oxford to introduce what they called ‘the research degree’ (the doctorate) into the faculty of English. They felt it had no place in the study of English, whether language or literature. Research, they thought, was not what scholars in the Humanities, or at least in the English faculty, did. Scholars had mastered their discipline, that is, they had read and meditated on, discussed with others, all that had been written in their field and this was evidenced by the M.A. degree. They then wrote the results of their meditations and discussions. Inside is written in my scraggly handwriting (now inexplicably called cursive): Ted Smith 12G.

Inside is written in my scraggly handwriting (now inexplicably called cursive): Ted Smith 12G.